It's a Camera-Off Kinda Day

Part 2 of series: Camera On or Camera Off

By late afternoon each Thursday, Sarah has noticed that she feels drained. Sarah’s typical week involves back-to-back virtual meetings, mostly with her camera on. As Sarah considers this pattern, she concludes that reading people via the camera is really taxing to her mentally and physically making her exhausted by the end of the week. To give herself a break, Sarah has started a practice of turning off the camera on Thursday afternoons and all day on Fridays so that she has a chance to recharge for the next week.

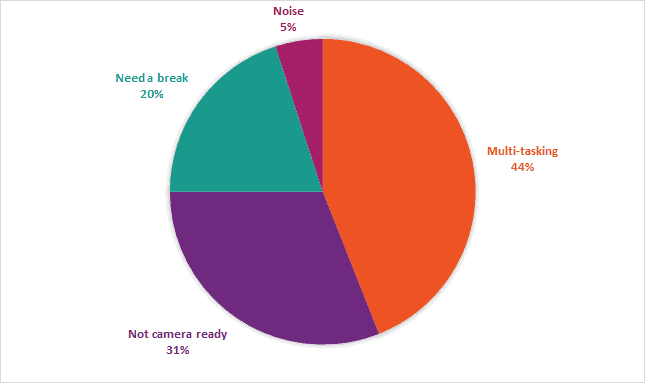

Does Sarah’s feeling of exhaustion resonate with you? Evans Consulting has done some research into this. What we found is that there are four main reasons our survey respondents turn their cameras off:

- Nearly half (44%) indicate that they are multi-tasking. Typical multi-tasking activities include shallow work (non-cognitive demanding tasks often performed while distracted, like email and tweaking slides or reports), social media (internet surfing or online games), or something personal (personal calls and texts, house chores).

- Almost one third (31%) turned their camera off because they were not “camera ready.” Other research indicates that not being camera-ready may not just be related to physical appearance, but could also be include background noise or activities that may detract from the meeting, e.g., a parent working from home.

- 1 in 5 respondents (20%) said that they need a break from the camera. One of the drivers for needing a break is dealing with technical difficulties and monitoring nonverbal cues from everyone in a meeting. Our brains work harder on camera.

- Finally, 5% said that there is too much noise going on where they are. When we work remotely, we are typically around others who create background noise or activities that distract from the meeting—for example, a working spouse on virtual calls, school-age children, or a pet.

These could be partially mitigated using the five key practices presented by Cal Newport in Deep Work (January 2016, three years before the pandemic started),

- Distance yourself from social media. It does not inherently contribute to your quality of life.

- Give yourself a strict time-period to spend working. This limits burnout and work creep, keeping you focused and urgent on your work. (e.g., working 9-5 with no work on weekends)

- Use commutes, exercise, cleaning, or other repetitive tasks to work out concepts. Rather than flick through radio stations or The Office repeats, use this time to work on the hard parts of your deep work.

- Prioritize with the 4DX Framework. In other words, continually apply the Eisenhower Matrix to your work:

- Do First (work on important tasks first)

- Schedule (important but not-so-urgent tasks)

- Delegate (less important tasks)

- Don’t Do (if not important or urgent)

- Notice Your Shallow Work to Better Avoid It. These are the “non-cognitively” demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted.

The future of Hybrid Work will see each of us attending meetings both in-person and virtually. The pandemic has made it more important for us to be more deliberate as we plan and execute activities as members of a Hybrid Workforce.

First, set and stick to defined work hours. Whatever work schedule you define, consistently stay with it. If you decide on no-work weekends, do not work weekends.

Second, drop social media and online gaming during work hours. These add no value to you or your organization.

Third, when you commute into the office, plan to reflect or think through the stickier parts of a problem – personal or professional.

Fourth, if you are working from home and a child needs help, or a pet wants attention, you let the meeting participants know, and they will understand. Interruptions like this will happen to all of us.

Finally, complete those “non-cognitive” or not-so-urgent tasks if you must multi-task during a virtual meeting. These tasks must be completed sometime. You can utilize your multi-tasking skills by closing out lower priority actions and tasks while listening to the meeting.

These are not new or radical suggestions developed in response to the pandemic. Newport presented these recommendations for effectiveness three years before COVID-19 disrupted workplace norms. The pandemic has simply shown how important it is to continuously view our work activities through the lens of these practices.

References

- Semczuk, Nina. “5 Practices from Deep Work by Cal Newport That’ll Change Your Life“ December 29, 2017.